In a courtroom at al-Maskobiyeh prison, two dark men sit on a wooden bench. They await their sentencing as their facial expressions move between boredom and mockery. The judge declares the decision to execute them, and as they are led to the gallows they sneer “hip hip, hooray.”

In 1934, the unpredictable tactics of Palestinian fighters Abu Jilda and al-'Armeet alarmed the English and the Zionists. It was for their attacks from the mountains that they were celebrated and eternalized in popular songs and tales.

Palestinian popular literature has always been full of tales. Some are laden with superstitions, while others are full of humor and tenderness, but all of them influenced Palestinian folklore. This unique outcome was born of exceptional circumstances, as it strengthened the people's need to identify with a specific history. As a result, folklore became a spontaneous expression of collective consciousness and personality.1

In light of the harsh conditions and consistent crises and attacks to which Palestinians were subjected in the early 1900s, there was a desperate need for a hero to take on the task of confronting oppression through retaliation. Palestinians used popular tales on a daily basis to raise morale and encourage patience and courage. No one would know the true source of these stories, and many alterations, additions, and exaggerations were included, placing its heroes in the same position as prophets. These stories did not, however, lose their primary purpose: to chronicle a nation's struggle against the Turkish, English and Zionist presence.2

These heroes would become legends, their fame bolstered by the fact that they remained anonymous soldiers with next to nothing known about them. They were neither known icons nor political leaders, but continued their resistance efforts in the dark. Tales of their exploits would spread so regularly among the people that there was no way of making sure of their origins or veracity. Over time, the stories would take on a mythical, often mesmerizing, quality. For this was the role that legends served at the time: to complement, align with, and fill in the gaps of reality.

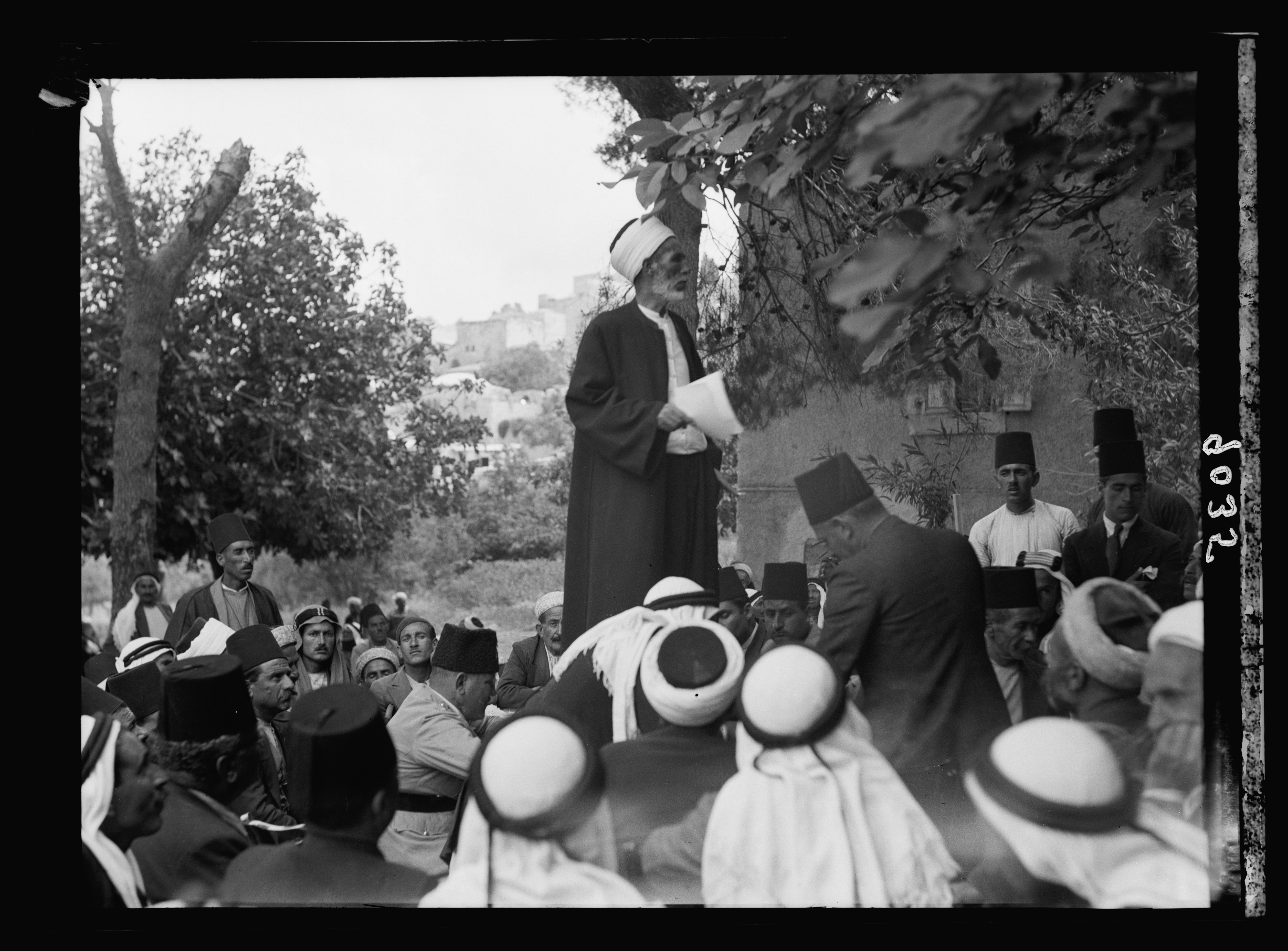

1936

PALESTINE

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS (G. ERIC AND EDITH MATSON PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION)

The first Palestinian guerrilla groups that engaged in armed struggle were Abu Kbari's group from the village of Beita, and Saleh Sleiqa's group from the village of Aqraba. They occupied a special place in Palestinian popular heritage. Their tales go on to say that British forces accused the brothers Ibrahim and Saleh Abu Sleiqa of killing the chief of Aqraba in 1922. Ibrahim was arrested a year later, while Saleh remained free.3 Ibrahim Abu Sleiqa met with Abu Kbari and Hameda al-Tamouni in Acre prison, and in their attempt to break out, Ibrahim killed an English soldier and was martyred after being shot by one of the guards. Abu Kbari and Hameda al-Tamouni were able to flee and Ibrahim's brother, Saleh Abu Sleiqa, met with them at a later stage. The three of them escaped to Jordan and continued to sneak into Palestine to perform continuous attacks on English patrols, always returning to Jordan after carrying out an attack. As Abu Kbari and Abu Sleiqa continued their raids, the English police never ceased in its attempt to capture them. This went on until Abu Kbari was martyred and Saleh was captured and sentenced to death. The sentence was later reduced to a life sentence.4

The heroics of Abu Kbari and Abu Sleiqa became a part of popular legends and tales, constantly told and retold by the people, and eternalized in poems and popular slogans:

والله ما بلبس ثوب لخضاري لو بحكموني حكم أبو كباري

راسي ما اطوّع لهيك زبونا

والله ما بلبس بدلة ركيكة لو بحبسوني حبس أبو سليقة

راسي ما اطوّع لهيك زبونا5

Despite the intertwining of imagination and reality in these popular tales, their influence on the balance of power in Palestine cannot be ignored; the sensation of danger, the fear of a surprise attack or harsh retribution, haunted British and Zionist forces, so much so that the British offered rewards to anyone who would find these heroes or provide leads on their whereabouts. Hebrew newspapers also relayed their news every day, and even documented their stories in some Hebrew songs.

In his diaries, Ariel Sharon refers to his trip from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv at the age of five, intimating his feeling of dread on the road: “I squatted over my seat deeply contemplating the Jewish highlands in an attempt to find any sign of Abu Jilda, the infamous Arab terrorist, who was specialized in setting up traps on the road to Jerusalem.”6

Abu Jilda and al-'Armeet were also a source of trepidation for spies and collaborators. Najati Sidqi, who was arrested and met the men in prison, says that al-'Armeet had told his mother from behind bars: “put a dagger in my grave, so I can settle my score with the snitch.”7

With the outbreak of the , it was no longer necessary to spread stories of revolution and heroism through exaggerated tales of grandeur. Palestinians forfeited the imagination and embraced reality, which was replete with stories of heroism ever since the revolt spread to Palestine's farthest reaches. Everyone became a possible hero, and all witnessed tens of battles in the combat areas of the mountains, villages, and cities.

Said Beit Iba was one of those heroes who became famous. He was able to escape from his jail cell and return to his family, the house of Rasheed. With the beginning of the 1936 Revolt, he began attacking English caravans, becoming a fugitive from then on. His group grew, and he was joined by many scout members and village residents from Nablus. During the Revolt, Said moved between Syria, Palestine, and Transjordan . Occupation forces tracked his family and relatives, demolishing their homes and destroying their properties in their attempt to capture him. Said had participated in many battles and survived several assassination attempts. His story ended when he was surrounded in the Battle of Beit Lid where he was martyred.8

Said Beit Iba and other heroes and fighters that partook in the armed struggle of the 1936 Revolt turned into icons chronicled by Palestinian popular tales. But their stories depended on their actual heroic deeds, unlike the legends before the Nakba .

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1Kanaana, Sharif. Al-Dar Dar Aboona: Dirasat fi Alturath Alsha'bi al-Filisteeni [T'is Our Father's House: Studies in Palestinian Popular Folklore]. Ramallah: Shuruq Publishing House, 2013, p. 24

- 2Zayyad, Tawfiq. Suwar Min al-Adab al-Sha'bi al-Filastini [Pictures from Palestinian Popular Literature]. 2nd ed. Akka: Matba'at Abu Rahmun, 1994.

- 3Kabaha, Mustafa, and Nimer, Sarhan. Sijil al-Qada wa al-Thuwar wa al-Mutatau'een Lithawrat 1936-1939 [A Record of Leaders, Revolutionaries, and volunteers in the Revolution of 1936-1939]. Kufr Qare': Dar al-Huda, 2009.

- 4Aqrabawi, Hamza. “Saleh Sleiqa: Min Ruwwad al-Nidal al-Sha'bi fi Filastin [Saleh Sleiqa: A Figurehead of Popular Struggle in Palestine]” 2011, https://pulpit.alwatanvoice.com/content/print/239515.html .

- 5Ibid.

- 6Sharon, Ariel. Mudhakarat Ariel Sharon [Ariel Sharon's Memoirs]. Translated by Antwan Obeid. Beirut, Lebanon: Maktabat Bisan. 1992, p. 26.

- 7Sidqi, Najati. Muthakarat Najati Sidqi [The Memoirs of Najati Sidqi]. Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies, 2001, p. 102.

- 8Kabaha and Sarhan. Record of Leaders, Revolutionaries, and volunteers, p. 398