When one thinks of “appreciating art,” what may come to mind is an image of two graceful individuals entering a museum with a white stone front. They would give in their tickets and roam between the exhibitions. They may stand in front of a square painting for a prolonged period of time, arching their heads left and right in an attempt to “feel” something. While 97% of the painting constitutes a single color, one of the individuals would mutter something about what it reminds her of. Her partner would nod approvingly, and they would return to their lives, arguing over what they are to have for dinner.

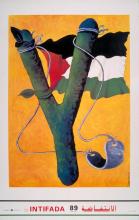

But appreciating art during the years of the First Intifada, both in Palestine and in neighboring states, was a perpetual project that cannot be confined to a tranquil spring afternoon. It was not exclusive to a select few, but open to everyone,1 as was the process of creating it. It was a part of the daily rituals evoked by the uprising.2

Like many other fields that were transformed by the Intifada to better suit the needs of the times—including education, trade and agriculture—art in Palestine complimented resistance. Considered a popular daily venture, art would produce its own tools, style, audience and artists, away from the dictates of “high art” and its history.

Reclaiming the portrait

In the times of the first Intifada, Palestinians reclaimed their streets, their schools, and their gardens, seeking to redefine them and open a road for the imagination. They even reclaimed the walls, treating them as one would a white canvas to be filled as they wish.

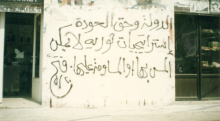

It was not a simple act of rebellion, but a response to a practical need. At the time, newspapers were under severe censorship and many were even stopped for a period of time. It was for that reason that the need for an alternative source of information arose.

Therefore, while using the walls as a space for creative expression, art also had an inherent utility. Those who resisted the army would convert the walls into a channel used to disseminate information to specific individuals through symbols and signs. This resulted in the pursuit of graffiti artists and slogan writers, deeming them wanted by the occupation.

The occupation distributed statements under the emblem of “a declaration of warning,” which cautioned Palestinians from writing on the walls, and demanded they remove the slogans scrawled on the walls of their homes. The penalty would reach a monetary fine of 1500 NIS, and on some occasions, it would entail actual jail time of up to five years. This sentencing is still active to the present day.3

The battle between Palestinians and the occupation would then shift to the walls of homes. It was even given a name: the battle of brushes and paint.

Nijma Ali, a Jerusalemite and a researcher, lived through the days of brushes and paint during the First Intifada. She explains that Palestinians in Jerusalem were forced to travel to Tel Aviv to purchase paint and brushes in order to avoid drawing attention to themselves, because purchasing them in Jerusalem would mean initiating a “crime.”

Despite the efforts to stifle the ability to draw on the walls through its criminalization, Palestinians innovated methods of protecting themselves and ensuring the continuation of this act. For instance, they would cover the graffiti with white solution when occupation forces passed by, so that the wall would appear white. Once the soldiers left, they would spray the walls with water and the paintings and slogans would re-appear as they were.

"Marj Ibn Amer" show in al-Hakawati Theatre in Jerusalem 1989

When prison becomes a musical instrument

Music is also part of the story of the Israeli pursuit of artists during the First Intifada. Like the rest of the arts, songs become spaces for the articulation of the uprising.

Artists such as Waleed Abed al-Salam, Thaer Barghouthi, Mustafa al-Kurd, Abu Nisreen, and groups such as Sharaf (1988), Istiqlal (1988), and Jafra (1989) all emerged during the uprising, and made songs directed towards its participants.4

The consequences would include arrests, as was the case of Mohammad Ata Khattab. Khattab was arrested every year of the uprising for several months at a time.5

The first revolutionary cassette was released under the title Sharar (“Spark”), composed by the artist Suhail Khoury. When the Israeli intelligence caught 15,000 copies a car, they sentenced him to seven months in prison. This was in 1988, when Israeli forces also arrested Waseem Kurdi, placing each in a separate prison. Kurdi was taken to Junaid prison, while Khoury was held in Atlit prison, and Ata in Ansar prison.

As with most political detainees, prison sharpened the imagination of the three artists. When Kurdi's family paid him a visit inside the prison, he leaked through the nets the lyrics of “The Sun Danced on Our Swords.” The family then passed on the lyrics to the popular arts troupe, el Funoun, and from there the group transmitted them to Suheil Khoury in his own prison. Khoury composed the melody, to become the first song.

Mohammad Atta, who knew how to play the flute on the dangling electricity pipes in the prison, had driven the Israeli prison guards mad as they searched for the source of the music from the prison cells. After searching his room dozens of times, he had convinced them that the music is coming from a punctured toothpaste tube. When he had received the song curated by Khoury and Kurdi, Atta began to sketch the artistic dance in his mind.

It was this constant transport between different prison cells that birthed one of the most important works of the el Funoun group, known as “Marj ibn Amir .”

This did not happen without the attempts of the authorities to control it by enforcing penalties on artistic activism. Numerous national events were cancelled, and cultural centers were closed. One example is the Hakawati Theatre, which was closed for 24 hours under the pretext of security as soon as intelligence heard news about the event. Adding to that, the army would also erect checkpoints to prevent the gathering of audiences.

However, this did not stop artists. Many would walk the long distances on foot just to reach the location.

The creation of color

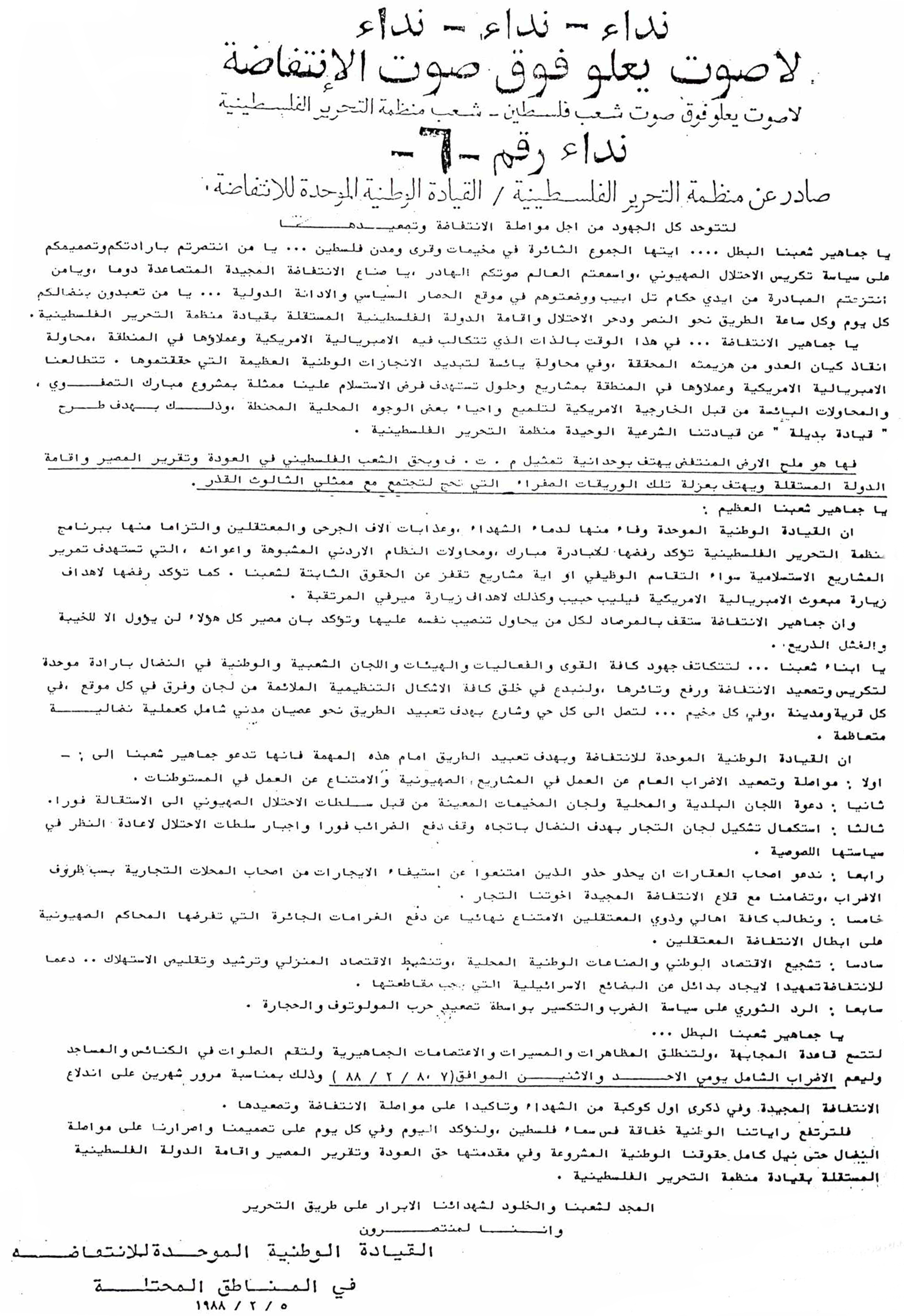

On February 5 1988, the uprising's sixth Communique was released. It called for the “support of national economy, local products, and the stimulation of household economies.” It also pushed for the “rationalization of consumption and shrinking it to bolster the uprising in preparation for finding alternatives to Israeli products, which must be boycotted.”

A statement by the Unified National Leadership of the Uprising in 2/5/1988

For many years, the siege meant that artists relied on Israeli products, and for artists the call meant that they forgo their brushes, paint and canvases. Social solidarity and the call for boycott, and artists' commitment to boycotting Israeli art products, pushed a search for creative alternatives for artists to continue their artistic passion.6

Nabil Anani was one of those artists. The uprising had brought him back to his childhood hometown of Hebron, where he began to study and examine the colors of tanning and henna. He moved on to research, alongside his colleagues, the colors that can be yielded by blending various spices. With this, their journey of experimenting to create local colors began.

Anani began to paint on wood. He would cut the drawings with a saw, then after flogging and pinning it, he would make a background to keep it fixed. He would then transition to coloring. Anani had discussed with his comrades the idea of producing paint, and tried all conceivable possibilities. He used henna, ink, and spices such as Cumin and Sumac. “I failed many times,” he says, “but with constant experimentation I found a way to preserve the colors on the canvas through working on leather, where the colors would not be entirely dry, but half dry.”

Alongside Anani, many other artists introduced their locally-made artistic products. Suleiman Mansour utilized mud and hay, which are often used in the making of jugs and whitewash. Taysir Barakat used natural dye extracted from the peels of pomegranate and onions, used in the past to color silk strings for embroidery. Another artist, Jawad Ibrahim, utilized local stones to curate various small sculptures.

“Exit into the Light” was the first painting that artist Nabil Anani created during the uprising. It was exhibited in the Hakawati Theatre in Jerusalem, while Anani continued his experimentation. He used other materials such as wood and copper, while continuing to use leather and various raw materials for approximately six years.

The artists were pursued just as others were, either through interrogations, or through the sources of painting. In 1981, Suleiman Mansour's exhibition was closed down, and he was incarcerated. Issam Bader was also jailed, while Anani was banned from travel.

“It was our duty, as artists during the uprising, to create a framework and to take a role in what was happening as required by collective responsibility,” said Anani. “Considering that we are a people carrying a message, partnering with our people was a must. We are an integral part of them.”

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1Al-Madhun, Rub'i. Intifada Filistinya: Alhaikal Altanthimi wa Asaleeb al-‘Amal [A Palestinian Intifada: Organizational Structure and Modes of Action]. Acre: Mu'assasat al-Thaqafa al-Filastiniyya, Dar Aswar, 1989.

- 2Schiff, Zeev. Yaari, Ehud. “Intifada” Sagiv, David. Jerusalem, Tel Aviv: Dar Shoken Publishing House, 1990.

- 3Mohammad, Ibrahim. Mohammad, Tareq. Shiarat al-Intifada: Dirasa wa Tawtheeq [Slogans of the Intifada: Study and Documentation]. Almarkaz al-Filastini lil I'lam [Palinfo], 1991, p. 35

- 4Nubani, Yamin. Thaer Al-Barghouthi, Laheeb al-ughniya al-thawriyya fi Intifadat al-hajar [Thaer Barghouthi, the fire of the revolutionary song in the Intifada of the Stones]. WAFA Agency. August 15, 2015. link

- 5Ali, Nijma. Al-ughniya al-siyasiyya al-filastiniyya bayn al-intifadatain [The Palestinian Political Song Between Two Intifadas]. Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 2009. (unpublished senior thesis)

- 6From an interview with the artist Nabil Anani, August 20th, 2015 at the International Academy of Art - Ramallah.