They were watching from the rooftop. The first signal is set off. The boy runs inside the mosque. He relays a message to the imam, who in turn climbs the stairs up the minaret, reaching for the megaphone.

The second signal is seen. Yesterday's wanted man starts to prepare. His bag is ready and he is very familiar with the path to the cave. The most important thing is for the youth to buy him more time.

The Israeli army jeep reaches the entrance of the village, only to be received by a flaming tire. The soldier driving the vehicle smiles comfortably, slowing down to circumvent the tire. At the furthest point of the curve, he loses control. He tries to turn right as quickly as possible but is met with a hail of potatoes filled with nails. The vehicle is brought to a screeching halt.

The process flows smoothly. Everyone in the village knows their role and executes it without hesitation. People were the spokes of a turning wheel that protected the nascent Intifada.

When the First Intifada took off, the spirit of resilience was overwhelming. Things could no longer proceed without the will of the people. What the people ate was no longer dictated by the Israeli authorities' control over produce. Military vehicles were no longer allowed to enter and leave villages whenever they wanted. The villages had returned to the people, and with it came the responsibility of protection and defense. Perhaps this is the concrete face of freedom: when a group of people are in open revolt, a sense of responsibility takes over as they start to organize their own lives.

Preventing the success of Israeli army raids and the obstruction of their movements was one of the most important forms of protection. Minarets and towers turned into alarm systems, alerting residents to the movements of the occupation and informing them of their imminent intrusion.1

Palestinian Flag on Mosque in Beit Sahour 1989

Photo by Daniel Hughes

Other methods emerged to reclaim the streets, setting them on fire under the feet of the soldiers. Many times the asphalt turned into a sheet covered with broken glass, spikes, and oil slicks, all used to puncture holes in the tires of the army's vehicles or to make them lose control by skidding off the road.2

These attempts continued and evolved to include a combination of acts of sabotage. Protesters would place a burning tire after a dangerous curve in the street. A few meters away from that they would pour oil. In the event that the soldier driving the army Jeep would swerve to avoid the flaming tire, he would run into the pool of oil, where the vehicle would skid on top of the previously laid potatoes. If the vehicle was a tank that had chains or tracks, blankets on the road were the best way to obstruct its movement, as they got caught in the tracks.3

The trips made by army vehicles during every raid pushed the Israeli army to sometimes re-occupy an entire village in the hopes of controlling its inner movements, but that was no easy task. The defensive tactics that the Palestinians had adopted were not merely reactions to intrusions or to their dangers; the Palestinians also chose the time and place of the clashes, which they willingly took part in.4

Widespread engagement in popular resistance created the need for easily available resistance tools—the use of darts, slingshots, and iron balls.5 Bows and arrows were used against Jewish settlers living in the middle of Hebron6, and even rudimentary pistols were invented, made from a steel pipe that contained one shot.7

Military jeep of occupying Israeli soldiers in Beit Sahur, durng November 1989.

Photography: Daniel Hughes

The birth of a new society

When the friends of a martyr sing at his funeral, “Oh mother of the martyr, ululate, all the young men are your children” it is more than a one-sided vow. This motherhood, which transcends bloodlines, is also the promise of Palestinian women to their sons' comrades. “This is my son,” screams one of the women, clinging to a young man as he is apprehended. The soldiers realize that their arrest will be harder than they expected.

This was one way that Palestinian women entered the struggle, placing them at the heart of the First Intifada's experiences. Such participation marginalized the voices that had called for their suppression. The Intifada had opened up spaces for Palestinian women in areas of defense and confrontation, away from the traditional roles they were “allowed” to take over.

These areas were connected to experiences gained in the Intifada. The social, political, and productive organization that the Intifada created necessitated the expansion of women's involvement in community work and the struggle as a whole.

To a large extent, the work of women was previously limited to charities. Now they enjoyed an extensive presence in unions, associations, and feminist and non-feminist organizations. This was only further bolstered by the emergence of nationalist female leaders. According to Rula Abu Dahou, the Palestinian women's movement shifted from a “social and charitable movement to a national political movement linked to the Palestinian political system and its national goals, and its most important post-1967 expressions.”

On a daily basis, the involvement of women was more direct. Until March 1988, 19 Palestinian women were killed by the Israeli occupation forces. Women also played a logistical role, creating supply lines to transfer rocks and empty bottles to demonstrators on the front lines.8

Economically, the emergence of new roles for women transformed them into productive elements within the popular struggle. Some of them manufactured and sold crafts, transferring the proceeds to those in need. Others turned gardens into cooperative farms to produce vegetables for food security while boycotting Israeli products and resisting the Israeli economic blockade.9 The women's committees participated in guiding housewives on how to save expenses, and took care of the families of martyrs, prisoners, and those who were injured. They also gathered blood units, donations, and foodstuffs for the needy.10

The changes in values and societal perceptions were not limited to women's roles; many customs were set aside during the Intifada as it embraced a new reality.

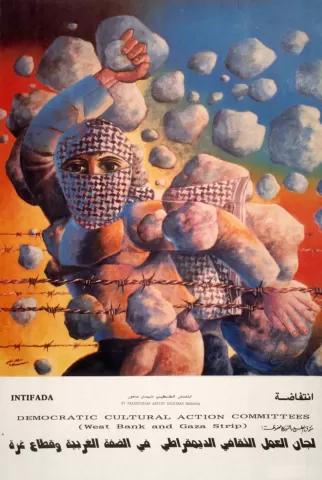

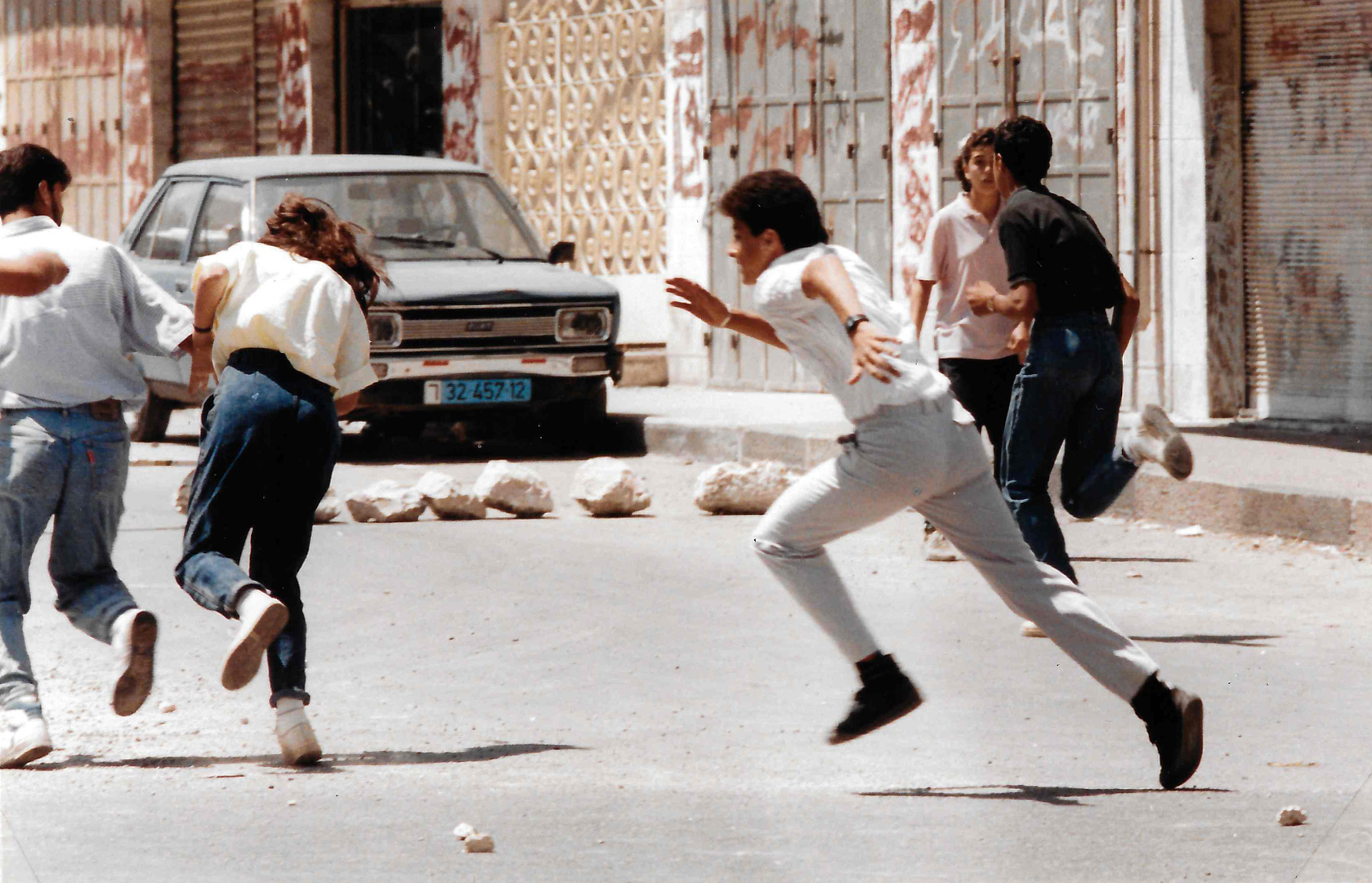

During the Clashes of the First Intifada in 1989

Mr. Samir Mustafa Abu Dheis Collection

At the height of the Intifada, Abdul Aziz Abu Hudba began to investigate the impact of the uprising on Palestinian traditions and customs during wedding occasions, studying fifteen Palestinian locations in the West Bank. He found that the dowry expenses had fallen by 50% in seven areas, and by 30% in two others. Furthermore, the bride and groom's separate pre-wedding parties were cancelled, while Dabka and zajal were absent from weddings.11

No society enters an uprising and comes out of it as it was before. Creating the type of social cohesion which would encourage resistance and sacrifice necessitated a shift in social values, one that gave each person a place of importance in the system of protection and confrontation.

Fields of victory

The stories, photos, and songs of the First Intifada have a certain charm to them. The uprising transformed neighborhoods into collectives which thought and fought in tandem. Of course, days and nights of work were behind this charm. If a village were to operate as a uniform body, it would have to be nourished.

The urgent need to build self-sufficiency in terms of foodstuffs and other products was the result of boycott efforts and Israeli closures. 45% of the Palestinian workforce which had hitherto been absorbed by the Israeli economy was unemployed on the eve of the Intifada. The fragile Palestinian economy was not in a position to provide an alternative. As a result, income levels fell by 35%, while the consumption of luxury products was considered to be in contradiction with national interests.12

The Market in Ramallah 1989

The transformation from a fragile economy into a self-sufficient model suffered many birth pangs. Yet with the continuation of political and economic coordination, priorities began to take on a clearer form, allowing for a focus on production. The production of grains tripled between 1978 and 1989, and the cultivation of olive trees increased. For the first time, the Occupied Territories reached the level of self-sufficiency in animal production, especially in white meat (poultry), whose production increased by 250%. The production of eggs increased by 70%, red meat by 8%, and diary products by 70%.13

Politically, the leadership responded to these requirements by allowing factories to break the strike and work to fill food gaps. The food industry experienced rapid growth, producing fruit juices, vegetables, fruits, canned meats, fast food, vegetable oils, furniture, leather products, textiles, tobacco, medical medicines, and even computer software.14

Naturally, these factories needed an agricultural renaissance to secure primary materials, which resulted in the formation of agricultural committees. They encouraged the cultivation of abandoned and neglected lands. In Beit Sahur, for example, a committee was established at the initiative of Bethlehem University. A center that sold seedlings, seeds, and fertilizers at a discount was established, while villagers provided guidance on how to cultivate the land. As rabbit breeding escalated, local blacksmiths trained themselves in building cages. Guidance was also offered for converting old refrigerators into incubators for raising chicks with the use of an electric adapter and an automobile battery. Thus, the domestic economy became a popular slogan, while the home-cultivated fields were affectionately dubbed “the fields of victory.”

Beit Sahur is known for the famous story of its eighteen cows, smuggled from Israel across the Green Line to strengthen the people's efforts to build an alternative economy. The cows provided local milk, allowing residents to give up Israeli dairy products. The cows were moved from house to house to avoid confiscation by the occupation, which had banned the cows and taken pains to locate them.

Agricultural relief committees were instrumental in transforming the Palestinian economy. These committees, made up of farmers and agricultural engineers, emerged from the pre-Intifada volunteer movement, quickly turning into an institution that sought to counter the Israeli policy of blocking Palestinian agricultural development. Before the Intifada, these same engineers and farmers had taken the initiative and become a volunteer organization in 1983. They attempted to protect the land from expropriation by planting and reusing it, providing Palestinian farmers with specialized technical guidance.

With the contribution of the agricultural committee and other Palestinian associations to the sector, the agricultural fields in the Gaza Strip increased from 13,000 dunams in 1980 to 21,000 in 1988. In general, local agriculture increased by 13%. This development helped the relief committees in providing loans to set up projects for arable land, and to provide partial compensation of $200 per farmer.15

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1Sayigh, Yezid. “Al-Intifada Tu'azziz Simatiha al-‘Askariyya [The Intifada Encourages its Military Characteristics]” Shu'un Filastiniyya, 181, Beirut: PLO Research Center, 1988, p. 123.

- 2Schiff, Zeev. Yaari, Ehud. “Intifada” Sagiv, David. Jerusalem, Tel Aviv: Dar Shoken Publishing House, 1990, p. 119.

- 3Haboush, Islam Suleiman. Dissertation. Al-Muqawama al-Sha'biyya Khilal al-Intifada al-Ula fi Qita' Ghazza ma Bayn 'Amay 1987-1994 [Popular Resistance in the Gaza Strip during the First Intifada between 1987-1994]. Gaza: Islamic University, 2015, p. 42.

- 4Schiff et al, Intifada, p. 119.

- 5Y.S. “Al-Intifada al-Muqatila [The Fighting Intifada]” Shu'un Filastiniyya, 179, Beirut: PLO Research Center, 1988.

- 6Editors. “Yawmiyyat: Muwjaz al-Waqa'i' al-Filastiniyya min 16/5/1989 ila 15/6/1989 [Daily updates: Digest of Palestinian Events between 16/5/1989 and 15/6/1989.” Shu'un Filastiniyya, 196, Beirut: PLO Research Center, 1989.

- 7Sayigh, "Intifada Characteristics," p. 124

- 8Al-Barghouti, Abdelatif. Al-Adab al-Sha'bi fi Dhil al-Intifada al-Filastiniyya [Popular Literature in the Shadow of the Intifada]. Al-Tayba: Markaz Ihya' al-Turath al-Arabi, 1990, p. 113.

- 9Al-Madhoun, Rub'i. Al-Intifada al-Filastiniyya: al-Haykal al-Tanzimi wa Asalib al-'Amal [The Palestinian Intifada: Organizational Structure and Methods of Action]. Acre: Dar al-Aswar, 1989, p. 42.

- 10Schiff et al, Intifada, p. 293.

- 11Abu Hudba, Adbul Aziz. “Ta'thir al-Intifada ‘ala ‘Adatina wa Taqalidina (fi al Afrah wa al-Atrah) [The Effects of the Intifada on Our Customs and Traditions (in Celebrations and in Mourning)]” Majallat al-Turath wa al-Mujtama', 2.5. 1990, p. 83.

- 12Al-Abed, George. “Al Mujtama' al-Madani fi Dhil al-Intifada [Civil Society in the Shadow of the Intifada]” Journal of Palestine Studies (Arabic), 5, 1991, p. 10.

- 13Ibid, pp. 10-13.

- 14Ibid.

- 15Habbush, Popular Resistance, pp. 157-158.