The peaked in the same year that it began, but its origins lie in the years before this date. A series of events served as harbingers of the Revolt, paving the way for its eventual outbreak. These events, despite their scattered incidence and varying levels of influence, contributed to reaching the confrontation point with the British Mandate and the Zionist movement on April 15 1936.

The Balfour Declaration represented the first chapter in the Palestinian struggle with the Zionist movement. Balfour's visit to Palestine and the trip of a Jewish delegation in search of Zionist aspirations in the country led to the mobilization of Arab groups and the formation of Islamic-Christian associations to resist colonialism. This would result in a series of conferences that reached an agreement to demand the complete independence of Palestine and the rejection of both the Balfour Declaration and the British Mandate.1

Jewish immigration to Palestine had reached its peak in the 1920s. This matter was not lost on Palestinians, who sensed what the authorities of the British Mandate were planning in relation to the Jews, the first signs of which was through the execution and privatization of major projects. This led to clashes and confrontations with British forces, and the rise of some groups that would target brokers.2

At the end of World War II, the Zionist leadership decided to undermine the British regime in Palestine as a prelude to the establishment of a Jewish state. One of its chosen tactics was the sponsorship of illegal mass Jewish immigration into the country over and above the official postwar annual quota. Between 1946 and 1948, tens of thousands of illegal immigrants were transported to Palestine from European ports. This scene was photographed at Haifa in the summer of 1946.

In response to the Mandate's policies of supporting the Zionist presence in Palestine, Palestinians escalated their attacks against Zionists and the different Zionist projects. Jewish immigrants flooded such projects and took over the resources and jobs from Palestinian laborers. The attacks would reach their peak between the years 1920 and 1921, resulting in the death of 30 Jews.3

In an attempt to bridge the political gap in the Palestinian context, Palestinians held a series of conferences which focused on the importance of national unity and Palestinian independence in the face of Zionist encroachment. This can be considered the start of the formal expression of Palestinian national identity.

Despite the intermittent stagnation of resistance before the Revolt, the years that preceded it witnessed mobilization in the direction of self-organization. There was a proliferation of associations, institutions, and scout groups, in addition to a large formation of women's institutions and groups, including Ri'ayat al-Tifil al-Yaffawiya in Jaffa , and al-Nahda al-Nisa'iya in Ramallah . These were two among a number of other branches of women's associations.4

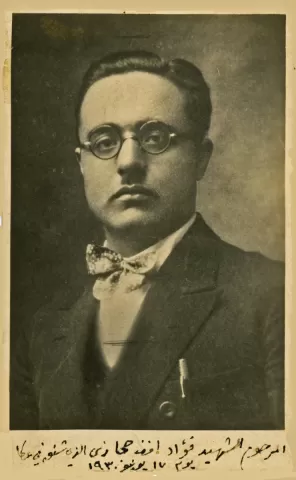

The ripples of the 1929 Buraq Uprising served as the most important factor in pushing the Palestinians toward revolt some seventeen years later, setting the parameters of their confrontation with the Zionists in the coming years. On August 15 1929, the Jews reached al-Buraq (the present-day Western Wall ) carrying Zionist flags and singing their Zionist national anthem, the Hatikva, or “the Hope,” asserting the day as the anniversary of the destruction of Solomon's temple. It coincided with the anniversary of the Prophet Mohammed's birth. These events led to violent confrontations in Jerusalem between the Palestinians and Jews5, and later extended to other Palestinian cities, heralding the start of the Buraq Revolution. It ended with a massive wave of arrests enacted by the authorities of the British Mandate against Palestinian youth in Safad, where 25 were sentenced to death. With pressure on the British High Commissioner, Britain was forced to lower the sentence to three executions—against Muhammad Jamjoum , Fouad Hijazi , and Atta al-Zeer , who later became symbols for the Palestinian struggle and a part of the Buraq Uprising until this day.6

The participation in the Buraq Uprising was not limited to men; Palestinian women sometimes participated in attacking British and Jewish military locations, as well as collecting donations and distributing them among the families of martyrs. Out of the 120 Palestinian martyrs in the Uprising, nine of them were women, most of them from villages: Aisha Abu Hasan from Attara, Izziya Muhammad Ali Salama from Qalunya , Jamila Muhammad Ahmad Alaz'ar from Sur Bahir , Nashaweek Hasan from Beit Safafa , Halima Yousef al-Ghandour and Mariam Ali Abu Mahmoud from Jaffa , Fatima Muhammad Ali Haj Muhammad from Bayt Daras , and two other women whose names remain unknown.7

Moreover, in the year 1929, the annual Women's Conference was held with the participation of 300 Palestinian women.8 They endorsed the resolutions of the Palestinian conferences, and decided to submit a memorandum to the High Commissioner, which included, inter alia, a rejection of the Balfour Declaration, a demand to prevent immigration to Palestine, the removal of Attorney General Norman Bentwich, and the repeal of the Collective Punishment Ordinance. The women also organized a protest of 80 cars that roamed Jerusalem in silence and passed in front of the consulates, reaching the High Commissioner and meeting him, where Matel Mughannam explained to him the demands of the women in English, followed by Tarab Abed al-Hadi in Arabic.9

The participating delegation in Cairo Women Conference of 1938 at Lydda Junction.

After two years, the executive committee of the Arab women's conference sent a telegram signed by Waheeda al-Khalidi and Matel Mughannam and dated July 22 1931, to the British authorities and the League of Nations, protesting the International Buraq Committee's report. The women also participated in a protest called for by Baheeja al-Nabulsi on August 25 1931, in support of the youth protests from the prior two days.10

This visit to the High Commissioner, coupled with the women's protests and other efforts by women's organizations and unions in Palestine, are only one way in which confrontation with the Mandate and Zionism played out.

The tactical and provocative role played by these conferences and protests was linked to resistance actions on the ground. It was a form of women's incorporation in political work, propagating a national discourse which places women at the center of events and makes them unique participants and mobilizers.

In the meantime, with the escalation of economic and material suppression, Palestinians had reached a point of no return, concluding that armed engagement and military confrontation with the English was vital to sinking the Zionist project and reclaiming Arab rights. Various clandestine armed groups were beginning to form and emerge in the 1920s, with the absence of a unified political infrastructure capable of directing the struggle against colonialism.

The Qassam Revolution was one manifestation of these armed groups. It was founded by the

Izzeddin al-Qassam was born in the town of Jabla, south of the Syrian city of Latakiya.

His father was Abd al-Qadir, his mother was Halima Qassab, his brother was Fakhr al-Din, and his sister was Nabiha. He had four half-brothers (through his father): Ahmad, Mustafa, Kamil, and Sharif.

He and his wife, Amina Na‘nu‘, had three daughters—Khadija, Aisha, and Maimana—and one son, Muhammad.

He completed his elementary education in his hometown at his father's elementary school (kuttab). At age fourteen he travelled to Cairo to attend the lectures given at al-Azhar Mosque by its most distinguished teachers, including the great reformer Shaykh Muhammad Abdu.

Having obtained the Ahliyya diploma, he returned to Jabla in 1903, where he succeeded his father in running the kuttab and teaching the basics of reading and writing, Qur'an memorization, and some modern subjects.

While he was in Egypt, a rebellion against the British occupation was led by Ahmad Urabi, an Egyptian army officer; it was unsuccessful. Qassam was deeply affected by the nationalist turmoil, as well as by the calls for reform, the maintenance of national unity, self-reliance, and resistance to foreign occupation.

Qassam became the imam of the Mansuri Mosque in Jabla and won people's respect through his sermons, lectures, and personal conduct. His reputation spread to neighboring regions.

After the Italian attack on Libya in 1911, Qassam called for aiding the Arab people of Libya through demonstrations and volunteering to fight on their side. He was among the first to join the revolt against French occupation on the Syrian coast in 1919–20 and fought valiantly against the French in the mountains surrounding the Citadel of Salah al-Din (Qal‘at Salah al-Din) north of Latakiya. Aware that he posed a threat to their control, the French authorities sentenced him to death.

In late 1920, Qassam, his family, and some companions sought refuge in the city of Haifa where he worked as a teacher in the Burj secondary school established by the Muslim Society, which was in charge of Islamic waqf in the district of Haifa. He then began to give religious lessons in the Istiqlal Mosque built by that same society, where his sermons excited much attention. A few years later he became imam and preacher of that mosque and founded a night school to offer adult literacy classes.

Qassam took part in founding a branch of the Society of Muslim Youth in Haifa and in July 1928, he was elected its president. That society was effective in spreading national consciousness among youth and men and in drawing them into its ranks.

In 1930, Qassam was appointed a religious official (ma'dhun) by the Shari‘a Court in Haifa. In this capacity, he traveled through the villages of the Galilee and got to know the people who lived there, all of which increased his reputation.

Qassam followed closely the growing menace of Zionism as a result of British support of the “Jewish National Home,” and he became convinced that Britain was the root cause of the problem and that only armed struggle could restrain the Zionist project. In his view, this could only be accomplished through sincerity of faith; abandonment of all party affiliation and family loyalty; cooperation; sacrifice; commitment to secrecy; and strict organization and timing. He combined this with a particular compassion toward the poor and those with very low income, and he sought continuously to improve their lot in life. He drew into his circle an ever increasing number of countryside inhabitants and elderly who migrated to Haifa to work in its port, industries and refinery, living in miserable suburbs to the east of the city. Many of them had been forced off their lands when these passed into Jewish hands.

Qassam was reluctant to declare jihad against British colonialism before his preparations were completed. However, the flood of mass Jewish immigration in the early 1930s, the increasing level of surveillance over his activities by the authorities, and his apprehension of a pre-emptive move against him all led him to declare jihad on the night of 12 November 1935 in Haifa. Along with eleven companions, he took to the forests of the village of Ya‘bad in the district of Jenin, where for six hours they fought a much larger British force on 20 November. Shaykh Qassam and four of his men were killed, and the others were wounded or captured.

In mourning, Haifa declared a general strike on 21 November 1935. All shops and restaurants closed their doors and thousands turned out to bid farewell to the fallen martyr and his companions in the largest funeral procession ever seen in that city.

Qassam was buried in the cemetery of Balad al-Shaykh in the Haifa district.

Izzeddin al-Qassam is regarded as the most venerable figure of Palestinian jihad, a source of inspiration for Palestinian resistance for succeeding generations. His assassination was to a large extent instrumental in igniting the Great Palestinian Rebellion (1936–39).

Sources

حموده، سميح. "الوعي والثورة: دراسة في حياة وجهاد الشيخ عز الدين القسّام". ط 2. القدس: جمعية الدراسات العربية، 1986.

الحوت، بيان نويهض. "القيادات والمؤسسات السياسية في فلسطين 1917-1948. بيروت: مؤسسة الدراسات الفلسطينية، 1981.

دروزة، محمد عزة. "مذكرات محمد عزة دروزة: سجل حافل بمسيرة الحركة العربية والقضية الفلسطينية خلال قرن من الزمن" (خمسة مجلدات). بيروت: دار الغرب الإسلامي، 1993.

عودة، زياد. "من رواد النضال في فلسطين 1929- 1948". عمان: دار الجليل للنشر والدراسات والأبحاث الفلسطينية، 1987.

"الموسوعة الفلسطينية"، القسم العام، المجلد الثالث. دمشق: هيئة الموسوعة الفلسطينية، 1984.

نافع، بشير موسى. "الشيخ عز الدين القسّام: مصلح وقائد ثورة". "حوليات القدس"، العدد 14، خريف- شتاء 2012، ص 6- 21.

نويهض، عجاج. "رجال من فلسطين". بيروت: منشورات فلسطين المحتلة، 1981.

Abdul Hadi, Mahdi, ed. Palestinian Personalities: A Biographic Dictionary. 2nd ed., rev. and updated. Jerusalem: Passia Publication, 2006.

In 1930, Izzeddin al-Qassam founded a military organization that opposed the Zionists and the British under the name of al-Kaf al-Aswad, or “The Black Hand.”12 By 1935 the number of its trained members ranged between 200-800 fighters.13 This organization targeted Jews in the Northern regions14, and it was said that they sought to clean out informants and spies. High levels of secrecy characterized their work, consisting of groups where only a quarter knew one another, while others in it did not know the rest of the groups at all.15 Women also took part in al-Kaf al-Aswad, especially in Jerusalem, where the active women worked to send threatening letters to the police. A number of women were arrested, tried in military courts, and sent to prison. One of them was Munira al-Khalidi, who was sent to prison in 1937.16

Regardless of the truth of this organization's founders and establishment, it undoubtedly contributed to the outbreak of the Great Revolt, alongside other organizations and groups, causing great harm to British and Zionist forces over years of upheaval and resistance.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1Nijim, Ibrahim, Amin Aqel, and Omar Abu al-Nasr, ed. Walid Khalidi. Jihad Filastin al-‘Arabiyya [Palestine's Arab Jihad]. Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies, 2009, p. 167.

- 2Aqrabawi, Hamza. “'Isabat Abu Kbari [Abu Kbari's Guerilla Group]” 2013, https://pulpit.alwatanvoice.com/articles/2013/10/13/308838.html

- 3Nijim. Palestine's Arab Jihad, p. 171.

- 4‘Alqam, Nabil. Tarikh al-Haraka al-Wataniyya al-Filastiniyya wa Dawr al-Mar'a Fiha [History of the Palestinian National Movement and the role of women in it]. Al-Bira: Markaz Dirasat al-Turath wa al-Mujtama', 2005, p. 81.

- 5Zuaiter, Akram. Mudhaqarat Akram Zuaiter: Bawakir al-Nidal [Akram Zuaiter's Memoirs: The Harbingers of Struggle]. Beirut: al-Mu'assasa al-Arabiyya lil Dirasat wa al-Nashr, 1994.

- 6Al-Hout, Bayan Nuwayhad. Al-Qiyadat wa al-Mu'assasat al-Siyasiyya fi Filastin 1917-1948 [Leaders and Political Institutions in Palestine 1917-1948]. Dar al-Huda, 1986.

- 7'Alqam. History of the Palestinian National Movement, p. 85.

- 8Nijim. Palestine's Arab Jihad, p. 174.

- 9'Alqam. History of the Palestinian National Movement, p. 86.

- 10'Alqam. History of the Palestinian National Movement, p. 87.

- 11Al-Mawsu'a al-Filastiniyya, p. 1948.

- 12Yaari, Ehud. Strike Terror: the Story of Fatah. Sabra Books, 1970, p. 41

- 13Segev, Tom. One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate. Macmillan, 2001, p. 360.

- 14Kedourie, Elie and Sylvia G. Haim. Zionism and Arabism in Palestine and Israel. Taylor & Francis, 1982, p. 63.

- 15‘Arrar, Abdul Aziz. “Al-Qada al-Fallahun fi Ma'ma'an al-Thawra al-Filastiniyya 1936-1939 [Peasant Leaders in the Heat of the Palestinian Revolution 1936-1939]” Dunia al-Watan, 2011. http://pulpit.alwatanvoice.com/content/print/220579.html

- 16Abdo, Janan. “Nariman Khurshayd wa Tanzim Zahratul Uqhuwan [Nariman Khurshayd and the Zahratul Uqhuwan Organization]” Jadaliyya, 2015. http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/21776/-%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%...

- 17'Arrar, "Peasant Leaders"

- 18Zuaiter. "Akram Zuaiter's Memoirs," p. 148.