In the turbulent political atmosphere of 1930s Palestine, political cartoons were much more than commentary on current affairs.

In 1930s Jerusalem, a young boy walks to school through the narrow, stone paved streets of the Old City. Every morning, as he reaches Damascus Gate, he passes a group of men gathered at a local coffee shop to listen to the latest news.

His name is Hazem Nusseibeh, and over eighty years later, he describes the scene to us from his home in Amman. “Big groups would come in from the villages near Jerusalem,” he says. “Their faces would be pink from all the walking and they would be carrying baskets of grapes and figs.”1

He describes how men from the villages would bring their harvest into the Old City to sell it at market, then go to a coffee shop where a man would read the newspaper to them.2 During the 1930s, only around one in five Palestinian-Arabs could read and write,3 so it was common to read newspapers aloud and show the pictures and cartoons to those who were illiterate.4 Through these gatherings, illustrated newspapers spread their message to a wide audience, shaping the political awareness of both literate and illiterate Palestinian Arabs.5

Drawing the Headlines

Gatherings like these were so widespread that after the 1929 Buraq Uprising, the British officials who had been sent to investigate the conflict reported back to His Majesty’s Government that “In almost every village there is someone who reads from the papers to the gatherings of those villagers who are illiterate. The Arab fallahin [smallholding farmers] and villagers are therefore probably more politically-minded than many of the people in Europe.”6

Political cartoons always appeared on the front page of these newspapers, providing sharp critiques of political negotiations, tactics and economic developments.7 Yet the woman who drew the most widely read cartoons in 1930s Palestine remains shrouded in mystery. All we know is that she was a Christian from Eastern Europe, and that the owner of the newspaper Falastin, ‘Isa Daud al-‘Isa, would think up the ideas for the cartoons and ask her to draw them. Her story was told over sixty years later, in an email from ‘Isa’s son to the American academic, Sandy Sufian, just a few years before the son passed away. Had it not been for this email, this mysterious woman would have disappeared from history entirely.

Sneaking Past The Censors

At first glance, there is also something mysterious about the cartoons themselves: the way they suddenly became popular, then just as suddenly faded back into obscurity. Before and after the 1936 Great Arab Revolt, political cartoons rarely appeared in Palestinian newspapers and as the conflict intensified, they became more frequent.8

It is no coincidence that as tensions in Palestine rose, British censorship of newspapers increased. Journalists were jailed, the publication of certain types of information was banned and daily newspapers were closed down for publishing “dangerous” articles. More than once, the British suspended all four Arabic dailies at the same time for what they considered to be provocative articles. During the early phase of the revolt, Arabic newspapers were suspended thirty-four times, while the Jewish press was suspended thirteen.9

In this repressive atmosphere, political cartoons were useful because subversive messages could be shifted from the text to the image, where they were more likely to pass censorship regulations.10

Though they may seem simple and direct, some of these cartoons contained multiple layers of symbolism.

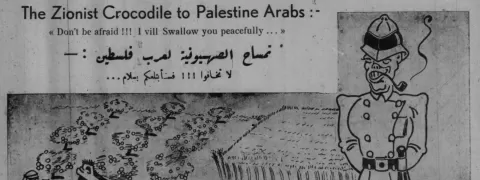

The June 1936 Falastin cartoon titled The Zionist Crocodile to Palestine Arabs tells a multifaceted story about the colonization of Palestine.

In the drawing, a tall British policeman in white uniform smokes a pipe. His face resembles a bulldog, in allusion to John Bull, a fictional character often used to symbolize Great Britain in cartoons at the time. The scholar Sandy Sufian remarks that “The officer is smiling, but this is not an innocent smile; it is more the sneer of a sly, criminal man. He is wearing heavy, cleated boots that match the black scales and claws of the Zionist crocodile, indicating congruence between the Zionists and the British.”11

The bug-eyed crocodile salivates as he prepares to devour Arab fallahin and their citrus groves, his tail emerging from the sea like a ship’s ramp. He embodies two key strategies of early Zionism: gaping jaws representing the colonization of indigenous land through Zionist land acquisition, and scaly tail alluding to the arrival of tens of thousands of European settler colonists to Palestine by ship.

In the 1930s, the displacement of fallahin through Zionist land purchases was a pressing economic issue. Fallahin debt and default on credit reached critical levels,12 made worse by the fact that British had started to tax many previously untaxed pieces of agricultural land.13 The fallahin resisted by joining trade unions and political organizations, and engaging in civil protest and cultivation disputes directed at the British, Zionists and the Palestinian upper class.

Worth A Thousand Words

At a library in Beirut, a middle-aged man puts on a set of rubber gloves, takes a small reel out of the archive and attaches it to the microfilm reader. The reader is a clunky grey machine that looks something like a PC from the 1980s. The Beirut-based library of the Institute of Palestinian Studies is one of the few places where these caricatures have been preserved, but sadly much else from this period has been lost forever.

Caught up in the fervor of revolt and faced with harsh British repression, it seems Palestinian revolutionaries and their supporters had little time to document their stories and preserve their history. Much of what had existed was lost a decade later in the Nakba, as Palestinians fled their homes in the face of danger from Zionist militias.15 In these rare drawings, we see some of the few remaining images that tell the story of an anti-colonial consciousness awakening in British Mandate Palestine.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1Nusseibeh, Hazem. Interview by Thoraya El Rayyes & Ibrahim Tarawneh, Amman (2015), sound recording.

- 2Ibid.

- 3Khalidi, Rashid. The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood. Beacon Press, 2007.

- 4Shaw, Sir Walter Sidney. Report of the Commission on the Palestine Disturbances of August, 1929: Evidence Heard During the 1st [-47th] Sittings, HM Stationery Office, 1930.

- 5Sufian, Sandy. “Anatomy of the 1936–39 Revolt: Images of the Body in Political Cartoons of Mandatory Palestine”, Journal of Palestine Studies 37, No.2 (2008).

- 6Shaw. Report of the Commission on the Palestine Disturbances.

- 7Sufian, Sandy. “Anatomy of the 1936–39 Revolt: Images of the Body in Political Cartoons of Mandatory Palestine”, Journal of Palestine Studies 37, No.2 (2008), p. 25.

- 8Ibid.

- 9Ibid, p. 27.

- 10Ibid.

- 11Ibid, p. 30.

- 12Ibid.

- 13Tamari, Salim, and Issam Nassar. The Storyteller of Jerusalem: the Life and Times Wasif Jawhariyyeh, 1904-1948, Olive Branch Press: 2013.

- 14Sufian. “Anatomy of the 1936–39 Revolt,” p. 30.

- 15Azoulay, Ariella. "Photographic Conditions: Looting, Archives, and the Figure of the" Infiltrator", Jerusalem Quarterly, No. 61 (2015): 6.