In Fathallah al-Bayari's restaurant, the food was the only constant. Everything else was unusual: money was not required to buy a meal, while the restaurant operated as a hotel for those who needed it. And amidst the tumult of the , serving food to the hungry every Friday became a revolutionary task.

Bayari provided free food to 1000 people, and housed nearly 500 families. He was not an exception, but one of many that published advertisements in local newspapers offering their volunteer work to help strengthen their community during the nascent revolution.

When the 1936 Revolt began in earnest, the Palestinians engaged in a general strike that encompassed the entire country. Material conditions did not make resistance easy, barely equipping the people with the means of casting off the yoke of colonialism. But Palestinians were well-aware that the path to revolution could not be paved with militant resolve and military power alone. Revolutionary action would need to be propped up by a supportive social network conducive to prolonged steadfastness.

After the declaration of their revolt and the creation of the Arab Higher Committee (Lajna) , Palestinians formed local committees known as the “National Committees,” whose function was to resolve problems that arose from the revolution. This included situations of emergency, such as the British Mandate's political and military escalation against the Revolt, or the general strike that pervaded the country's economic sphere.

The committees worked intensively to provide various forms of assistance to the people in the cities and villages, even mobilizing functional subcommittees according to circumstance. The aid committee, for instance, worked to secure and distribute donations.

The Jerusalem committee included several subcommittees, including the Automobile Committee, the Trades and Crafts Committee, the National Merchandise Promotion Committee, the Committee for the Needy and the Poor, the Lawyers Committee, the Medical Commission, and others.1

The funding of these committees was based on a number of sources, including individual donations from affluent residents of cities and villages, taxes paid by Arab employees in government departments, grants and individual donations from sympathizers in Arab countries, and finally, donations and food supplies provided by farmers.2

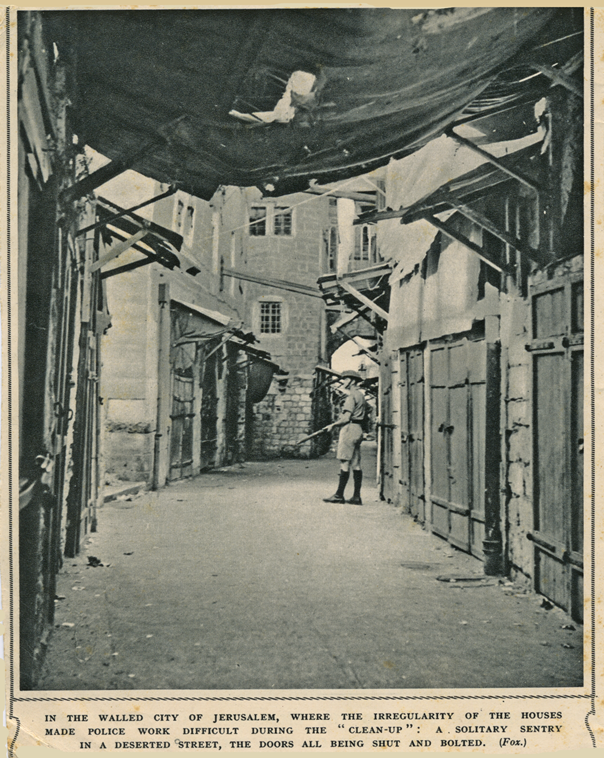

| British patrol during a curfew in one of old Jerusalems alleys during the 1936-1937 revolt. Clip reproduced from an unnamed British publication. |

Despite the funding, which enabled spending on local committees and ensuring that aid reached those in need, Palestinians also realized that in the absence of the financial backing of a state, new sources would have to be found to sustain the revolution's continuity and independence. The Barclays Bank was attacked, and £5,020 pounds were seized, in addition to £2000 from a post office. As a result, a committee that oversaw fiscal matters was formed in order to ensure the maximum use of these funds in order to spend them efficiently.3

Because of this high degree of organization among the Palestinians during their revolution, the leadership of the Revolt was able to help its revolutionaries and their families by providing them with incomes and provisional needs. A full-time fighter received between £1 to £6 per month; a combatant soldier received £2; a commanding officer was paid £4, and the assistant and commander were paid £6 and £9, respectively. All of these funds were made available through voluntary contributions collected by local committees from donors in towns and villages.4

With the expansion of the revolution, in-kind donations also increased to ease the conditions of the poor. Relatively well-off social segments, such as merchants, sellers, sailors, drivers, blacksmiths, and sheep traders, all joined the general climate in their own way. Some of the merchants in Nablus , for instance, handed over the keys of their stores to the National Strike Committees until the strike ended.5

| Palestinian Rebels parading in 1936 |

With the participation of a large number of men in the revolution, Palestinian women became a productive force. They were subject to increased punitive measures by the English that targeted the destruction of the families' food stocks.6 Rural women financed the revolution as best they could, selling their bracelets to provide weapons to the rebels. Women living in the cities collected money through their families, which was made more effective by the women's organizations based in the city.7

As a result of the Great Depression, severe poverty afflicted large segments of society. Heightened social solidarity was needed to enable people to receive even basic needs. Medical committees were formed to make treatment free for those in need.8 As a contribution to the revolution, many homeowners and real estate owners announced that their tenants would be exempted from paying their rents as long as the revolution continues.

Mohammed Yassin placed an advertisement in Filastin newspaper that stated:

“In order to encourage the strike, I am willing to return a month's wages to those who paid the rent in advance, and to deduct it for those who did not. If the strike continues for another month, I am prepared to proceed with this plan, that is, to waive the wages of another month, and so on. The monthly rent is fifty pounds, and I sacrifice this money for the sake of the nation.”9

Hence, donations became a main feature of the revolution. Newspapers were transformed into an important advertising medium for the dissemination of humanitarian affairs. The papers were filled with news of donations and humanitarian aid, from announcements of able families willing to host families in distress, to announcements of food donations. The owner of the Salanik Hotel placed an advertisement in Filastin, announcing the donation of 20 rooms. The hotel's coffee-maker chipped in and provided free coffee and tea to refugee families.10 Zeina Mohammed al-Qabbani placed an advertisement in the Al-Quds newspaper to provide free obstetric assistance in the district of Jaffa for ten days, as well as free care for the poor and disabled.11

The newspapers offered people a platform to announce the ways they wanted to contribute to the revolution. Local committees conducted a comprehensive survey by dividing cities into distribution areas in order to ensure the deliverance and access of donations to all those in need.12 Jaffa , for example, was divided into four zones to secure the requirements of the poor and needy.

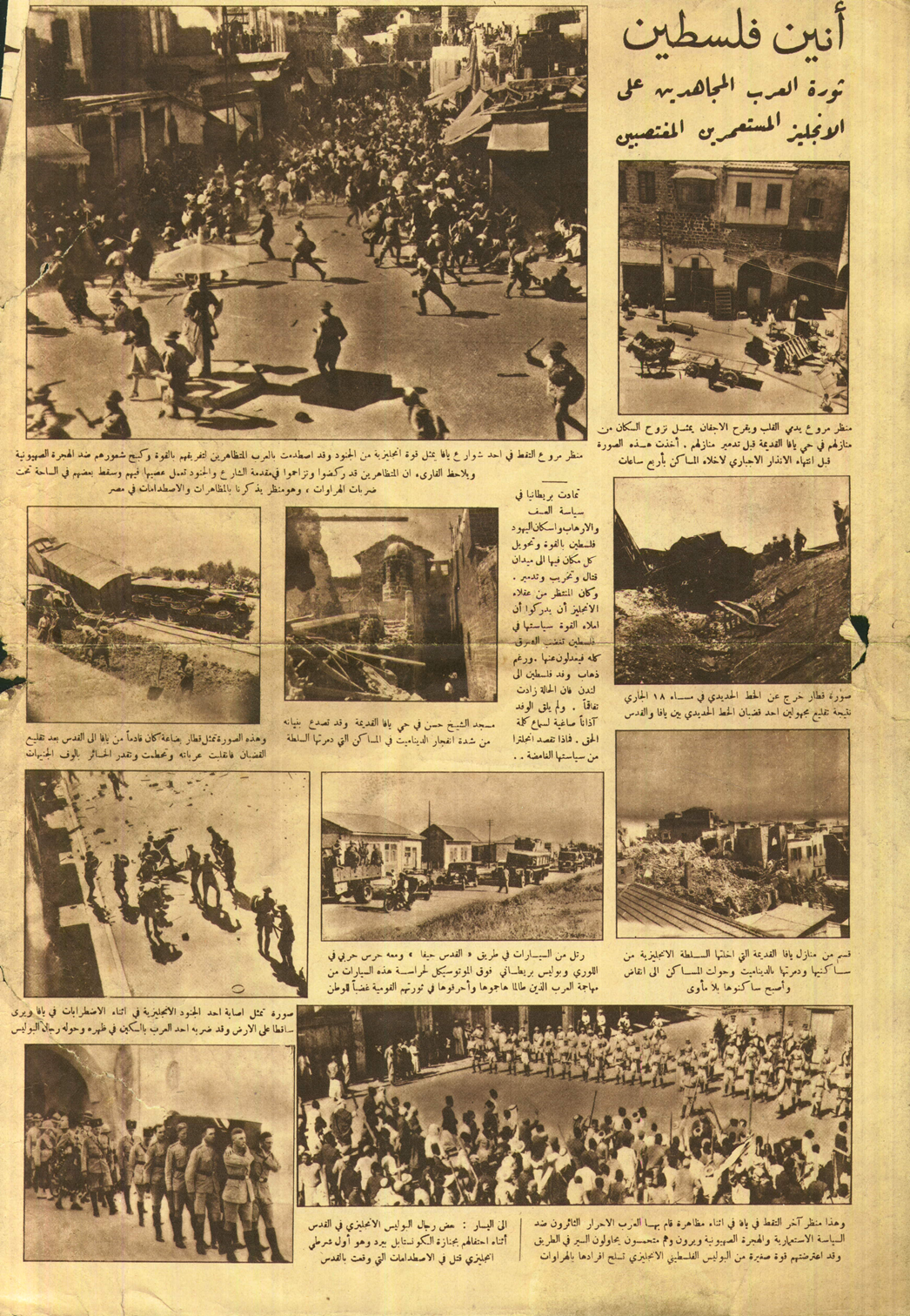

Images of the Palestine revolt of 1936-1939. The name of the publication is not available.

The Revolt witnessed what can be described as an exchange of mutual aid and sympathy between the Palestinian cities and rural areas, and individuals of different social backgrounds. This angered the English, who saw it as an unprecedented bridging of social divides.

The High Commissioner wrote a report to the Minister of Colonies on July 16 1936, stating:

“The work of aid and subsidies is practically limited to the residents of towns and large villages. The farmer does not have enough to feed himself these days, but he donates his crops to help his fellow townspeople. Regarding charitable work, there is a very high rate of direct individual effort. This effort is completely independent of the work of organized institutions. For example, a wealthy family takes care of one or two poor families. The trader supports his unemployed employees by paying their full wages or part of it. The individual helps the other, and it seems very likely that the current situation has created strong and brotherly feelings among the Muslims, which relieves organized charities of a lot of their work.”13

This interdependence and integration proved highly capable in strengthening Palestinian steadfastness, and contributed to the intensification of Palestinian guerrilla operations in the Northern and central regions of Palestine. There was also an increase in the ranks of revolutionaries and an improvement in their organization.14 This provoked and incensed the Zionist movement, who accused the Palestinian revolt of receiving material assistance from Britain's enemies abroad, but had no shred of evidence to prove it.15 An article published in Haaretz newspaper by Smilansky, in which he wrote about the collapse of hope and growing economic distress, stated:

“Our hopes are shattered, as if they were to be destroyed at home and outside the house. Every day there is distress and strangulation, either from the saboteurs, or from the severity of the economic distress.”16

The revolution began with disparate groups of revolutionaries and militants, but became a popular resistance movement and a collective struggle that served the people and the country. It neutralized colonial power and domination, thereby capturing the imagination of the Arabs. The Palestinian need for Arab support was more apparent than ever.

And this was what happened. Iraqi volunteers competed with a trained military force led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji . They entered Palestine and took the Triangle area (Nablus , Tulkarm , and Jenin ). The Arab capitals witnessed mass demonstrations and mobilized donations for the Arab national committees through activities and concerts dedicated to the Palestinian revolution.

A Demonstration in Jerusalem in 1934

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1see Palestine (Filastin) Newspaper, April 26 1936.

- 2Al-Hout, Bayan Nuwayhad. Al-Qiyadat wa al-Mu'assasat fi Filastin 1917-1948 [Leaders and Political Institutions in Palestine 1917-1948]. Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1981, p. 341.

- 3Yassin, Abdul-Qader. Thawrat 1936 al-Wataniyeh al-Filastiniyya: Ma'ali Ahmad Ismat, Waqa'i al-Thawra [The Palestinian National Revolution: Ahmed Ismat, Proceedings of the Revolution]. Cairo: Markaz al-Mahrousa lil Nashr wa al-Khadamat al-Sahafiyya wa al-Ma'lumat, 2007, p. 97.

- 4Ibid, pp. 81-82.

- 5See Palestine (Filastin) Newspaper, April 24 1936.

- 6Abdul Hadi, Fayha'. “Adwar al-mar'a al-filastiniyya fi al-thalathinat 1930 – al-musahama al-siyasiyya lil mar'a al-Filastiniyya [The role of the Palestinian Woman in the Thirties, the Political Participation of the Palestinian Woman]. Al- Bira: Markaz al-Mar'a al-Filastiniyya lil-Abhath wa al-Tawthiq, 2005, p. 63.

- 7Ibid, pp. 33-34.

- 8See Palestine (Filastin) Newspaper April 1936.

- 9See Palestine (Filastin) Newspaper, May 8 1936.

- 10See Palestine (Filastin) Newspaper, May 3 1936.

- 11Palestine (Filastin) Newspaper, May 13 1936.

- 12See Palestine (Filastin) Newspaper April 27 1936, on the division of Jaffa.

- 13al-Hout, Leaders and Political Institutions, p. 341.

- 14Al-Kayyali, Abdul-Wahhab. Tarikh Filastin al-Hadith [Palestine of Modern History]. Beirut: Al-Mu'assasa al-‘Arabiyya lil Dirasat wa al-Nashr, 1999, p. 293.

- 15al-Hout, Leaders and Political Institutions, p. 380.

- 16Dawaza, Mohammed Izzat. Maseerat al-Haraka al-Arabiya wa al-Qadiyya al-Filastiniyya [The Arab Movement and Palestine Cause]. Beirut: Dar al-Gharb al-Islami. Volume 3: 1993, p. 308.